The year was 1953. Dwight D. Eisenhower had just been inaugurated president of the United States and Salem was a bustling town, with area news focusing on the recent opening of several factories. Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away, a passing motorist made a grisly discovery the evening of Feb. 2 on a backroad outside of Niles, California.

William T. Pelton, a 26-year-old Salem native and World War II veteran, was found propped up against his sports car convertible riddled with nine bullets. Among his many wounds was a last kiss seared in lipstick on his forehead. His killer had apparently wiped his brow clean of blood in order to plant it.

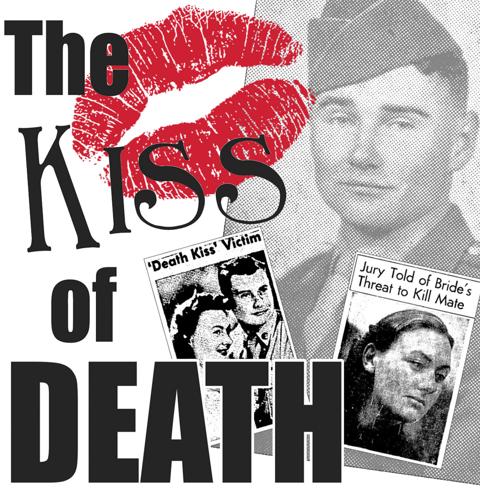

The incident, and ensuing nationwide search for the killer, became an international spectacle. The little town of Salem suddenly found itself the unlikely root of what became known as the “Kiss of Death Murder.”

The War Bride

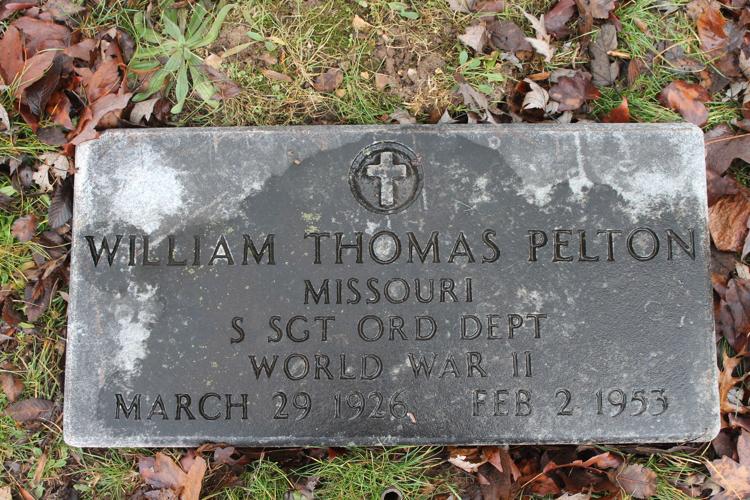

William “Bill” Pelton was born March 29, 1926, and grew up in Dent County, living on Washington Street. He worked at Vessie Wisdom’s service station as a teenager and was one of 44 graduates in Salem High School’s Class of 1944. News of the class’s graduation was shadowed at the time with stories of prayers in the lead up to the anticipated D-Day invasion. Like millions of other men of his generation, Pelton enlisted in the military upon receiving his diploma. He was joined by 10 of his classmates, including Salem’s Ted Ziske.

“The Bill Pelton I knew was honest and always on time for work,” Ziske says. “He was also absolutely an average young man. In appearance, intelligence and physique – he was average – and he never got in any trouble. I remember we were on an intramural basketball team together at one time, but again, we were very mediocre.”

Pelton was assigned to the 143rd Ordinance Battalion of the US Army during the war, rising in rank to staff sergeant. After the Allied victory in 1945, Pelton was stationed in Munich as part of the American occupation of Germany.

It was in Munich that Pelton’s eyes were caught by a strawberry-blonde Bavarian beauty six years his senior. To this day not much is known about the woman born Hildegarde Garni.

“There was an American bar in Munich which was really popular after the war, and I remember seeing her (Hildegarde) there often,” says Charles Grosse, another 1944 graduate of Salem High School who, like Pelton, was stationed in Munich. “She was very pretty and outgoing. We actually sat next to each other once at the bar when she was on a date there with another man.”

Hildegarde’s paper trail begins June 8, 1947, when she agreed to marry Pelton in Bavaria and take his surname. Her first mention in The Salem News came innocently enough on Aug. 7, 1947, announcing she’d arrived in Dent County at the home of her in-laws and was excited to begin her new life in the United States. The article reports she would be living in Salem for several weeks while awaiting Pelton, now stationed in New Jersey, to go on furlough and return home.

“I lived just down the road from the Peltons on Washington Street, and I remember bumping into her (Hildegarde) right in front of Vernon Butler’s house,” Grosse says. “We both recognized each other and were surprised to meet again in Salem. I asked what in the world she was doing here, and she said she’d just married Billy Pelton. I can’t say I was too surprised, there were a lot of women in Europe at the time who wanted to come to the USA as wives.”

In 1949, Pelton left the US Army and moved to California with Hildegarde to seek opportunity. By 1953, he was gainfully employed as an airline mechanic in San Francisco, had bought a fancy new convertible and seemed to have all the trappings of the American Dream.

Unfortunately, all was not was well with the Peltons.

On Jan. 6, 1953, Pelton obtained an interlocutory decree of divorce by default from Hildegarde without her knowledge. The two had reportedly been separated at least three times before the final break, and it was during their latest separation Pelton obtained the ruling while Hildegarde was living in Flagstaff, Arizona.

Hildegarde later said she was infuriated by Pelton’s action and left Arizona to confront her former husband in San Francisco. However, before leaving town, she purchased a Harrington and Richardson .22-caliber revolver.

If Pelton had known his drive with Hildegarde the evening of Feb. 2, 1953, would be his last he probably would have chosen a different route. The final destination was a deserted road outside Niles in Alameda County. We’ll never know the couple’s last words to one another, but what made international headlines were the results of the ensuing violence.

The Kiss of Death

Hildegarde shot Pelton nine times in his face, neck and head. His body had also been draped in a red hook rug while leaned up against his prized sports car. Prior to leaving the scene, Hildegarde took the time to wipe the blood from her now dead ex-husband’s face and leave one last mark of a kiss. She then wandered to a nearby California highway where she emerged from the evening fog in front of a passing motorist who gave her a ride to a bus station. From there, Hildegarde crossed the border to Tijuana, Mexico.

Investigators searching the murder scene found many different clues. Several bags packed with women’s clothing were abandoned in the vehicle. The .22-caliber murder weapon was located a short distance away wrapped in a bright multicolored scarf which was perforated with bullet holes. It had been tossed into a stand of nearby woods where it stood out among winter’s dead leaves and grass.

It didn’t take long for law enforcement to connect the murder to Hildegarde. The 32-year-old immigrant was then named a fugitive from the law and sought by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI.

News of the murder shook Dent County as it tantalized the rest of the country.

The Salem News ran a front-page story Feb. 7, 1953 detailing the crime alongside Pelton’s enlistment photo.

“Extreme interest in the sensational killing was shown by California newspapers,” The Salem News reported. “A long-distance call was received by The Salem News from a California newspaper in search of details of the background of the murder victim. Other calls were received in Salem from California in connection to the case.”

Ziske says he heard about Pelton’s untimely demise from a classmate.

“I was pretty shocked. It was very unusual and unexpected,” Ziske says. “The incongruity that Bill Pelton could be involved in such a thing. He was absolutely the last person you’d expect to be murdered in such a way.”

Grosse agrees that the news was confounding.

“Billy Pelton was not dominating or cruel in any way, and I can’t imagine him being unfaithful,” Grosse says. “I kept trying to explain to myself how such a thing could happen. I wouldn’t have dreamed in my wildest dreams that this boy, who I used to walk to school with, would end up shot so many times in a convertible in California.”

The national press began referring to the crime as the “Kiss of Death Murder” and “Death with a Kiss Case.”

Hildegarde also became simply referred to as “The War Bride.”

Pelton’s body was returned to Salem where a funeral was held at the Spencer Funeral Home with Reverend Paul Mooney conducting services. Pelton received full military honors and was interred in the southwest corner of Cedar Grove Cemetery on Feb. 4, 1953.

Pelton’s parents left Salem to live in Kansas City.

Mexico to Manhattan

Hildegarde’s Mexican adventure was short-lived. Soon after her arrival she was arrested on a charge of vagrancy and sent back across the border. She spent a night in the border town jail of Negolas, Arizona, under the assumed-name of Helen Curtis. However, Hildegarde was released before her true identity was revealed by a routine check of her fingerprints by the FBI.

The prized foreign fugitive was once again at-large in America.

The fumbled arrest caused a sensation in the press and headlines once again warned readers to be on the lookout for the “The War Bride,” now said to not only be a man-killer but master of deception.

The Salem News joined the spectacle with another front-page article on March 5, 1953.

“Search for missing GI Bride of Pelton extends to Mexico,” read the headline. The story details that Hildegarde was, “believed to have been seen in Guaymas, Mexico, about 200 miles south of Negolas on the Gulf of Mexico.”

In reality, however, the elusive German fled north, hitchhiking to New York City and taking up residence at a cheap Manhattan apartment on West 47th Street. Hildegarde was paying rent with a job working at a concession stand of a Broadway movie theater.

So it was for Hildegarde, until March 31, 1953, when she was arrested after leaving the theater by FBI agents. The marquee title that loomed over her while being taken into custody was Alfred Hitchcock’s “I Confess.”

Newspapers once again trumpeted the news, running salacious stories detailing that Hildegarde flirted with FBI agents and had confessed to killing Pelton, at one point even admitting, “I kissed him after the shooting.”

She reportedly never elaborated whether the embrace was out of love or spite.

“It was very dramatic thing to do, to kill him and then kiss him,” Ziske says. “Germans are very interesting people. They tend to overdo most everything they set their mind to. Maybe she read about that kind of thing, the kiss of death, at any rate that right there makes the whole case fascinating.”

Jailed to Germany

The justice system of the 1950s was swift.

Hildegarde was put on trial just three months after her arrest in June of 1953. The most compelling testimony came from Mrs. John Nunez, an acquaintance of the Peltons during their time together in California.

Mrs. Nunez testified she was riding in a car with Hildegarde and her husband, when Hildegarde said, “I’m going to kill him. No kidding. I’m going to kill him.”

Mrs. Nunez said Pelton’s retort was, “I’m getting tired of waiting for you to do it.”

A jury of six men and six women found Hildegarde guilty of second-degree murder, rejecting the prosecution’s argument for the first degree, but holding her responsible for Pelton’s death.

Superior Judge O.D. Hamilton Jr. sentenced Hildegarde to five years to life in the California Institute for Women in Corona, California. She received the verdict in stride, and was photographed showing no emotion at all, while clutching a white handkerchief to her breast and keeping her eyes riveted on the leg of the counsel table in front of her.

The Salem News ran the announcement on the front page July 16, 1953, summing up the year-long ordeal by calling it a “sensational murder,” which warranted or not, had gained nationwide publicity.

After serving less than four years in prison, Hildegarde made the news one last time after accepting a conditional parole and being released from jail in February of 1957. As part of the agreement, Hildegarde was deported from the United States and ordered to return to her native Deutschland, then known as West Germany. If still alive, she is 96 years old.

Hildegarde appeared one last time on The Salem News’ front page with the parole announcement on Feb. 7, 1957. It was four years to the day the news of Pelton’s murder first broke in his hometown.

From there, Hildegarde’s paper trail ends with her return to Europe. What trouble or reform she undertook while back in Germany will likely forever remain a mystery.